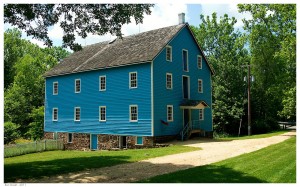

Atsion: Part 3 – To the Modern Day

This is the final article in a three part series looking at the history of the ghost town of Atsion. You can find part one

This is the final article in a three part series looking at the history of the ghost town of Atsion. You can find part one

This is part two of a three part series looking at the history of the ghost town of Atsion. You can find part one at

Henry Drinker, a wealthy Quaker merchant in Philadelphia, wrote: “I expect it will be nothing new to hear that we Iron Masters are in general

In the Pine Barrens: The Beauty and the Wealth of a Land of Desolation Originally published in the New York Tribune, August 6, 1893. You

Brendan T. Byrne State Forest, formerly known as Lebanon State Forest, is located in the northern part of the New Jersey Pinelands. It’s location and

Wharton State Forest is the largest, and perhaps the best, place to begin a Pine Barrens adventure. With over 115,000 acres of land spread between

It all started with a road map of New Jersey. A little north of the Red Lion Circle, in the heart of the Burlington County

Hidden back in the woods near Buckingham, the deserted station stop of the Pennsylvania Railroad that brought visitors from Philadelphia to Long Branch in the

The tavern was a building that, in colonial America, was second in importance only to the meetinghouse. Here a person could hear the news, find

I set off on todays adventure, as I have so many in the past, following the path of the late historian Henry Charlton Beck. Beck

Since 2002, NJPineBarrens.com has been bringing the wonders of the New Jersey Pine Barrens to the internet. With articles, a vibrant discussion forum, interactive maps, and image galleries there is sure to be something for everyone here.

Welcome!

© 2024 NJPineBarrens.com – All Rights Reserved