I set off on todays adventure, as I have so many in the past, following the path of the late historian Henry Charlton Beck. Beck explored many of the “forgotten towns” of Southern New Jersey while writing for the Camden Courier Post in the 1930s and continued writing about them up to his death in 1965.

The trail today would take me through Crosswicks, home of the famous Quaker meeting house with a cannon ball from the Revolutionary War embedded in it. For Beck the journey along the old country lanes and byways must have taken forever, but the modern highways of Rt. 295 and Rt. 195 made short work of my trip from Princeton. The way to Crosswicks is through Yardville, and almost immediately after exiting the highway time seems to begin to turn back. Old houses line even older roads from a time before a committee or developer named them, but by virtue of what little hamlet they’d bring you to. The area is full of them: Crosswicks-Hamilton Square Road; Crosswicks-Chesterfield Road who’s name inverts once you get closer to Chesterfield; Georgetown-Chesterfield Road – they go on and on.

The description Thomas Gordon gives of Crosswicks in his New Jersey Gazetteer of 1834 still seems a good description of the town:

“… contains from 40-50 dwellings, a very large Quaker meeting house and school, 4 taverns, 5 or 6 stores, a saw mill and grost mill; the village is pleasantly situated in a fertile country, who’s soil is sandy loam; near the town is a bed of iron ore, from which considerable quantities are taken to the furnaces in the lower part of the county.”

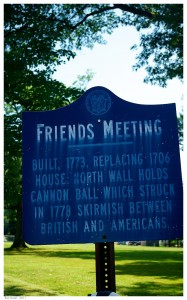

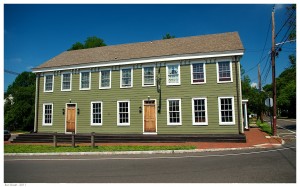

Dominating the village green of Crosswicks for the last two hundred and thirty years is a large brick Quaker meetinghouse, built in 1773 at a cost of $3750. This is the third meetinghouse located on the site since the congregation began meeting in 1693. During the Revolutionary War both the British and the Colonials used the meetinghouse as barracks, which proved to be difficult for the pacifist Quakers who still continued to hold meetings there during the conflict. Within the meetinghouse is an old bog iron stove from Atsion, one of three known to still exist.

Crosswicks was the scene of a skirmish between the British and the Americans during the Revolution. In 1778, as General Clinton and his troops were retreating back towards New York the militia destroyed the bridge over Crosswicks Creek. There were several exchanges of fire including some of the British field pieces, with one wayward British cannonball embedding itself in the side of the meetinghouse. At some point in time a caretaker dug the cannon ball out of the wall and kept it at his house for safekeeping. After his death, sometime in the early 20th century, the ball was returned and a mason hired to plaster it back into place. The ball is still there today, visible between two windows on the upper story.

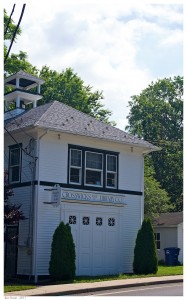

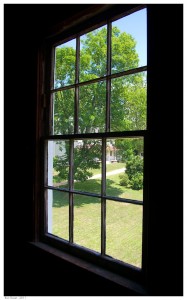

Walking through the town is like stepping back in time. The Crosswicks Library is located in the building formerly occupied by the Union Fire Company. The old post office, further down the road, is quaint in its red siding. Old houses line the street perilously close to the road, old “wavey glass” still in many of their windowpanes.

At the end of the town is the Crosswicks Inn, the latest name for a structure that served as a stagecoach stop throughout the 18th century. Across from there is the old Hamilton Uniforms Factory, originally the Edgar Brick & Sons Mince Meat Factory. The rambling weathered building is from 1874 and appears all but abandoned.

The road from Crosswicks led on to Chesterfield, once Recklesstown, passing along picturesque farms and a mix of new and old houses. Recklesstown, they say, comes from the Reckless family, one of whom died trying to apprehend John Bacon at the Battle of Cedar Bridge in 1782. In 1834 Gordon found the town to contain “a tavern, store, and 10 or 12 dwellings…” Today the tavern and store are still in operation and not many more dwellings line the ancient roads. It’s a quiet, tranquil place although my presence photographing a tree in the general store parking lot seemed to annoy one person who sneered at me as he drove past in his truck.

The trip to Arneytown from Chesterfield continued on through this historic area. Old houses, some clapboard, some brick, mixed in here and there along tree-lined roads that all of a sudden opened up alongside vast farm fields. Province Line Road cuts right into Arneytown, along the old Arneytown Inn that has recently been purchased by a history-minded couple intent on restoring and preserving it. Here, too, historic homes line the street and, at the bend of the road opposite the tavern, lays a little known graveyard said to contain the bones of the notorious Pine Robber John Bacon.

The cemetery is a small, unkempt affair. It’s not marked with any signs and the headstones are perilously close to the road. They stretch back into the undergrowth in what seem to be three rows. Doubtless many more stones than just the one that marked Bacon’s grave have been lost to time. Here lie the Harrises, Blacks, Tiltons, Schooleys and Lawries. Nearly forgotten as time – and the road nearby – passes on.

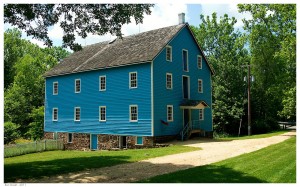

From there, Province Line Road takes you up near Walnford in Upper Freehold Township. Crossing a picturesque single lane bridge you arrive at the back of Historic Walnford Village, now part of the Monmouth County Park System.

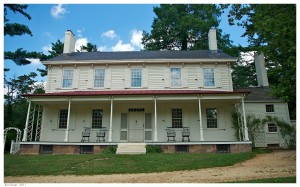

The mansion there is similar to the ones at Batsto and Atsion – grandiose country manors that housed masters of industry that the towns centered upon. At Batsto it was iron. At Walnford it was a gristmill, sawmill, fulling mill, blacksmith and cooper ships, tenant homes, farm buildings, and an orchard. Richard Waln, a Philadelphia Quaker, purchased the mills and surrounding land to build a country estate in 1772. He built a beautiful 7 bedroom, five thousand square foot home overlooking the millpond across from the gristmill. It is said that Richard sympathized with the British, which makes sense given the amount of sympathy the British had in old Monmouth County. His political leanings put him at risk to have his property confiscated, but he seems to have dodged that particular bullet when he was arrested. The property stayed in the Waln family until 1973 when it passed to the Mullen family, who still operate a farm nearby. They deeded what is now Historic Walnford Village to the county in 1985.

The mansion is open to visitors, and the similarities to the old Atsion mansion are striking. The kitchen, with its giant brick hearth and ovens, is roughly the same size as Atsion. Some of the mantles around the fireplaces are marble, and all of them have cast iron firebacks. Though the inscriptions are worn over time most seem to be from Pennsylvania furnaces, notably one from Mary Ann Furnace near Hanover, Pennsylvania. Unlike Atsion, however, there are very un-Quaker decorative flourishes throughout the house. In the family room off the formal parlor there are two closets with beautiful scalloped woodwork above decorative flourished wooden shelves. Each bedroom has its own closet, a sign of wealth and prestige back in the 18th century.

The house once housed a post office. Kept by “Aunt” Sally Waln, who was widowed after only two years of marriage. By all accounts she was a strong woman, simultaneously tending the post office, managing the gristmill operation, and taking care of her elderly mother. The room that the post office was housed in eventually became a kitchen in the 1970s and, while there are no appliances in it anymore, the color and style of cabinetry harks back to that brown and gold era.

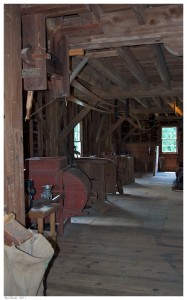

In 1822 the gristmill, which had been doing less and less business in the face of neighboring competitors, burnt down. Other Walns who had moved away argued against rebuilding it, but Sally was determined since the mill had been so important to the Waln family in the past. Today the mill is much as it was back then. Leather belts cross overhead, connecting the driving power of the mill turbine to various machines located on the three floors. A pulley elevator, guarded by a sleeping cat when I visited, is in the front of the building, still ready to lower milled corn and grain down to a waiting wagon that will never come again.

Here, then, is the picturesque land where Burlington and Monmouth County meet. A land of slow, narrow country lanes bordered by historic houses, inns, and farms. A land steeped in the time and tradition of bygone days of the past.