The name Red Oak Grove, for many, may be unheard of, but for Pine Barrens enthusiasts, it is an enigma bound within Pandora’s Box. Its only evidence is the remains of several foundation pits, and a name listed on nineteenth century maps. It is as elusive as it is intriguing. Chatter abounds on Pine Barrens list-serves about it, and many seem to be the one who knows its full tale. Often, these are the very same people who have placed their faith in Henry Beck’s accounts of the small village.

Now, I am not one to claim that I know everything there is to know about Red Oak Grove, but I have come a long way in piecing together much of its tale. There is much still unknown about this area, but first let us begin with those common notions that are accepted and held as fact.

Part of the reason for scant information about Red Oak Grove, is that it disappeared. Its inhabitants either moved away or died out for one reason or another. Next, it was not a major hotbed of excitement, but rather a small, quiet rural village situated well away from larger towns. Further, since it was never incorporated as its own municipal entity, there are few public documents pertaining to its existence. And finally, since it disappeared more than a century ago, few living inhabitants of this region know anything about the area.

The hunt for this little village has been exhausting, in the sense that it has nearly exhausted every research venue that exists. However, the search has also been somewhat fruitful. What follows is incomplete, but is also the most comprehensive and detailed history of this elusive village.

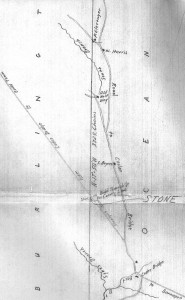

The exact origins of Red Oak Grove are hard to pin down. The village came into existence sometime around the early to mid 1840s. It was originally a village of Pemberton Township, Burlington County, New Jersey. Two of its early inhabitants were a man by the name of Samuel Bryant and his wife Leann. In 1846 Bryant purchased a large parcel of timber land in Burlington County with a mortgage, built a house and lived there with his wife, this was in the vicinity now known as Red Oak Grove. [1] Whether there were many others living nearby is unknown as there are few documents pertaining to this area. However, this was not Bryant’s only property; he also owned several acres of a development on the Pole Bridge Stream, near Mt. Misery. [2]

April 10, 1851 marked the earliest known “official” record for Red Oak Grove as Samuel Bryant applied to establish a Post Office at his home. [3] This post office was listed in several National and State gazetteers as located in Burlington County, New Jersey.[4] On March 26, 1855 the Red Oak Grove post office of Burlington County was officially closed;[5.] and, in 1856 Bryant’s mortgage for Red Oak Grove was foreclosed upon.[6] He died in 1857 and his property was divided and sold to several individuals. One portion was sold to William Irick[7], a founding executive of the Medford Bank and owner of numerous sawmills and lumber tracts; another portion was sold to Lewis Neill,[8] a fire-brick maker from Philadelphia, and later a portion of the same estate was sold to Andrew McCall,[9] Methodist Minister and manager of Neill’s brick works.

William Irick held the deed to the lion’s share of Red Oak Grove, but the land was still being used for lumber. Christopher Estlow, a Burlington County farmer, began to operate the mill on Irick’s behalf. He moved to the region from Hanover Township[10], farther to the north and west. In 1858, Estlow re-established the Red Oak Grove post office, situating it in Lacey Township, Ocean County[11] and, by 1859 he purchased the Red Oak Grove tract and launched headlong into the lumber industry.[12.]

In 1856 Lewis Neill began a fire-brick and pottery factory on a small part of the property that was known as Red Oak Grove.[13] However, Neill’s property was not located in Pemberton Township, Burlington County, but in Lacey Township, Ocean County. Red Oak Grove crossed both township and county borders, but still consisted of adjoining properties. His brick works, commonly known today as the “Union Clay Works,” was becoming more successful and soon he took on three business partners under the trade name of “Lewis Neill and Company.”[14] Neill began to buy more adjacent properties and expand the size of his land holdings at the factory, and in 1858 an article appeared in the New Jersey Courier, a local newspaper, telling about the new clay industry that was operating in the area.[15]

In 1858, a tobacconist and Methodist Minister from Philadelphia named Andrew McCall bought a parcel adjacent to the clay works and moved there. The deed to his parcel listed the property as Red Oak Grove.[16] McCall soon began working as the manager of the clay works[17] and probably also provided for the spiritual development of its workers as well.

1858 was a banner year for the area. By this time, it was becoming necessary that a school be established for educating the local children. Christopher Estlow, Lewis Neill, and Samuel Webb applied to the Ocean County Freeholders to establish a school district at an area they called “Plainville.”[18] This “Plainville” was essentially the area situated around Neill’s factory, and was comprised of portions of what used to be Red Oak Grove.

In 1860, Christopher Estlow closed the Post Office at Red Oak Grove, and established one at Woodmansie, only about two miles to the north.[19] Woodmansie was a better area for Estlow due to the fact that the Raritan and Delaware Bay Railroad was planned to (and eventually did) pass right through it.

In 1862, Lewis Neill began to sell off portions of his property. His first major sale was to Charles Middleton – a Gloucester County iron master who, like Estlow and Irick, was active in the lumber industry – and consisted of a parcel just north of the clay works.[20] He changed directions with his business, and by 1864 was buying land along the Barnegat Bay to use for raising oysters and growing salt hay.[21] By 1865 his shift away from brick-making was complete when he sold his factory to a brick and terra-cotta making operation from Brooklyn, New York and moved to Monmouth County, New Jersey.[22] Joseph K. Brick, the new owner of Neill’s works got the factory up and operating rather quickly. However, within two years of the sale Joseph Brick died and ownership of the company passed to his wife, Julia. Amid scandal and intrigue, Brick’s company continued operating underneath the direction of Julia Brick and Edward D. White.[23] By November of 1867 the factory was firing clay pipe again and ready for distribution.[24] The company was renamed the Brooklyn Clay Retort and Fire Brick Company[25], and operated only a short while longer until law-suits over Joseph Brick’s estate made keeping this factory afloat too cumbersome. The factory closed down sometime in the late 1860s.[26]

In 1873 Andrew McCall, unable to pay his mortgage, sold his property at Red Oak Grove. The buyer was Charles Middleton, who undoubtedly needed the land for his growing lumber business.[27.] McCall moved to Manchester Village, only several miles away, and served the community as a clergyman.[28] Also in the 1870s, Christopher Estlow expanded his lumber operations and bought the old mill at Wells Mills, located near Waretown. He later expanded this operation to include additional saw mills and ran a very successful lumber company.

The Red Oak Grove area saw a lull in activity after the 1870s. With the exception of Middleton’s lumber industry nearby there was little happening in the region. The clay works was dormant; abandoned with a full stock of wares and unfired kilns. The only industry extensive enough to maintain a good population, cranberry growing, was situated up near Woodmansie. Part of the reason for this lull could be directly related to the Panic of 1873, a major depression that nearly crippled the American economy. As a result, many banks and small businesses closed their doors bankrupt.

Mining reemerged in this region, however, just before the turn of the century. Near Woodmansie were the Old Half Way clay mines, the same that were used to supply Neill’s works. The mines were purchased by Alfred A. Adams, a hotel owner in Woodmansie, who started mining and selling local clay again in 1896.[29] Part of the impetus for this was talk of a new rail spur being laid through Woodmansie, Union Clay Works, Red Oak Grove, and all the way out to Tuckerton. In 1895, the Brighton Land Company filed plans for a development called “Red Oak Park,” which was to be situated just north of the defunct “Union” clay works.[30] The development was quite large and spanned the Ocean County / Burlington County border. When the railroad failed to go through, however, the development failed with it and was bankrupted by the early 1900s.[31]

As for the defunct clay works, it stayed dormant until 1897 when it was bequeathed to the Brooklyn Memorial Hospital in Julia Brick’s will.[32] By this point, the majority of any settlement, or hope for settlement, in the Plainville / Red Oak Grove area was finished. The villages of Red Oak Grove, Plainville, and “Union Clay Works” were abandoned. And, with the exception of the occasional squatter, tenant, or local agricultural worker, these villages were uninhabited memories of places long forgotten.

On account of its pertinent role in the lumber trade, especially early in its existence, it is highly plausible that Red Oak Grove was named simply for that reason – it possessed a concentration of Red Oaks. Red Oak is still today a highly coveted lumber for furniture, and decorative woodwork. As millers were the first to name the region, perhaps their reason was very direct. On the other hand, Red Oak Grove is a name that occurs throughout the United States. There are Red Oak Groves, dating from the mid to late nineteenth century, in Iowa, Kentucky, Alabama, Michigan, and many other states. So, it is also very possible that this was a popular name to use at that time. However, I will leave that for future research, or the reader to decide.

This is the tale of Red Oak Grove as far as the documentary record will allow. I am positive that more information exists somewhere, but as of yet it is unwilling to be found. Perhaps in years to come, more information will be uncovered to further flesh out the life and times of this forgotten village. But, for now, the tale is at an end.

This article was first published on NJPineBarrens.com in 2006.

Notes:

1 Ocean County. Deed Book 17 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks 1856), 102.

2 Ocean County. Deed Book 23 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks 1856), 382.

3 Jennifer Lynch. Personal Correspondence. 4 Richard S. Fisher. A New and Complete Statistical Gazetteer of the United States of America (XX:XXXXX 1853), 714. See also J. Calvin Smith. Harper’s Statistical Gazetteer of the World (XX: Harper’s 1855), 1458; and, United States Postal Service. List of Post Offices in the United States (Washington, D.C.: United States Postal Service 1859), A031.

5 Lynch, Personal Correspondence.

6 Ocean County, Deed Book 17, 102.

7 Ibid.

8 Ocean County. Deed Book 11 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks 1856), 73.

9 Ocean County. Deed Book 15 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks 1858), 265.

10 United States Census Bureau. 1840 Census of Burlington County (Washington, D.C.: United States Census Bureau 1840).

11 Lynch, Personal Correspondence.

12 Ocean County. Deed Book 17 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks 1856), 107.

13 United States Census. 1860 Census of Dover Township, Ocean County, New Jersey (Toms River: Ocean County Historical Society); see also George H. Cook. Annual Report of the State Geologist for the Year 1878 (New Brunswick: Geological Survey of New Jersey 1878), 55-6.

14 One of these partners, as a matter of fact, was Lewis C. Cassidy – a well-known Philadelphia attorney who lobbied the Pennsylvania Legislature in 1872 to extend suffrage to women. Interestingly, one person he used as an example for his argument happened to be Margery McManus, wife of another partner in the clay works.

15 New Jersey Courier. November 21, 1867.

16 Ocean County. Deed Book 15 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks 1858), 265.

17 Cook, Annual Report, 55.

18 Ocean County. Miscellaneous Records Book 1 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks 1858), 74.

19 Lynch, Personal Correspondence; see also, Major E. M. Woodward and John F. Hageman. History of Burlington and Mercer Counties, New Jersey, with Biographical Sketches of Many of Their Prominent Men (Philadelphia: Everts and Peck 1883), 508.

20 Ocean County. Deed Book 25 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks 1862), 101.

21 Ocean County. Deed Book 29 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks 1864), 359; see also, Ocean County. Deed Book 37 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks 1866), 230.

22 Ocean County. Deed Book 35 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks 1865), 5,8; see also, Ocean County. Deed Book 55 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks 1865), 141.

23 Ocean County, Deed Book 35; Ocean County, Deed Book 55; Ocean County Wills Book 3 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks), 36; Ocean County Wills Book 9 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks) 341, 346; see also, Brooklyn Landmarks Preservation Commission [BLPC]. Brooklyn Clay Retort and Fire Brick Works Storehouse (Brooklyn: Brooklyn Landmarks Preservation Commission), 4.

24 NJ Courier, November 21, 1867.

25 BLPC, Storehouse, 4.

26 Cook, Annual Report, 55-6.

27 Ocean County. Deed Book 70 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks 1873), 304.

28 United States Census Bureau. 1870 Census of Manchester Township, Ocean County, New Jersey (Toms River: Ocean County Historical Society).

29 George H. Cook. Annual Report of the State Geologist for the Year 1897 (New Brunswick: Geological Survey of New Jersey 1897), 331.

30 Ocean County. Map A-18 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks 1895).

31 State of New Jersey. Corporate Records (Trenton: Division of Commercial Recording).

32 Ocean County. Deed Book 357 (Toms River: Ocean County Clerks 1897), 190.