The country from Evesham down to Tuckerton has all the appearance of its original wildness—few houses or settlements appear. Pine and oak woods on both sides of the road perpetually ; and for at least 30 miles of the road, the bushes on either side fill up the whole road, which is scarcely the single path which one wagon fills. We met nothing almost on the road to turn us out. I could thus have a very good conception of how the country looked in the hands of the aborigines, some few of whom still linger about.

Was much interested to see the formidable ruins of Atsion iron works, (27½ miles). They looked as picturesque as the ruins of abbeys, &c., in pictures. There were dams, forges, furnaces, storehouses, a dozen houses and lots for the men, and the whole comprising a town ; a place once overwhelming the ear with the din of unceasing ponderous hammers, or alarming the sight with fire and smoke, and smutty and sweating Vulcans. Now, all is hushed; no wheels turn, no fires blaze, the houses are unroofed, and the frames &c., have fallen down, and not a foot of the busy workmen is seen.

Little Egg harbour, (now a poor country and population,) was once a place (in my grandfather’s time, when he went there to trade &c.) of great commerce and prosperity. The little river there used to be filled with masted vessels. It was a place rich in money. As farming was little attended to, taverns and boarding houses were filled with comers and goers. Hundreds of men were engaged in the swamps cutting cedar, and saw-mills were numerous and always in business, cutting cedar and pine boards. The Forks of Egg harbor was the place of chief prosperity ; many shipyards were there ; vessels were built and loaded out to the West Indies ; New York and Philadelphia, and the southern and eastern cities, received their chief supply of shingles, boards, and iron, from this place. The trade too, in iron-castings, while the fuel there was abundant, was very great. The numerous workmen, all without dependence, on cultivation of the soil, required constant supplies of beef, pork, flour, groceries, &c. from abroad. Even the women wore more of imported apparel than in any other country places. Merchants from New York and Philadelphia went there occasionally in such numbers that the inns and boarding houses could not contain them, and they had to be distributed among private houses. On such occasions they would club and have a general dance, and other like entertainments.

Sometimes rich cargoes came ashore on the beach, and were brought up the river for public sale, and brought there many traders to buy.

The vessels from New York and New England on trading voyages were numerous before the Revolution. The inlet was formerly the best on the coast ; and many vessels destined for Philadelphia in the winter, because of the ice on the Delaware, made into Egg harbor river, and there sold out their cargoes to trades from New York and Philadelphia.

In these times Great Egg harbor had little or no distinction. Its inlet and advantages were not good. It since enjoys more than Little Egg harbor. Now both those places do their chief business in taking cord wood, especially pine, to the cities ; but formerly they did none of that, when fuel was cheaper and easier procured.

In the time of the revolutionary war, Little Egg harbor river was a good refuge for our privateers, or their prizes. The British, aware of it, endeavoured to avenge themselves. They entered it in light vessels and destroyed Chestnut neck, a town of about 20 houses, which have not been since rebuilt.

Count Pulaski, with his legion was down there, and had an action with the British in the Revolution.

There used to be a considerable exportation of sassafras from Egg harbor. Some vessels went direct to Holland with it “north about,” to avoid, I believe, some British orders of trade therein. The Dutch made it into a beverage which they sold under the name of sloop. This commerce existed before the war of the Revolution.

When I ride over these lands and see so much soil whitened and glistened in the sun, especially in the woods where vegetation cannot conceal, I am forcibly persuaded that all these Jersey lands were once traversed by the finny monsters of the great Atlantic deep ; and where the formal pine trees tower, there the billows rolled!

We arrived safely at Tuckerton at 7 o’clock in the evening. It proved to be a much neater and more civilized place than I expected. Several houses were painted, and were of boards, save Tucker’s store, which was of brick. I should suppose it contains fifty buildings ; twenty houses are on the main street. It has a Methodists’ and Friends’ meeting house ; a mill dam and grist and saw-mill, and near it a wind-mill to make salt. This last article is made with success and profit. The work cost $4000. The people here have several fields planted with the castor-bean plant and have two or three mills to grind it. They find it very profitable. Their chief export has been pine wood.

Friday morning, at 7 o’clock, I left Tuckerton with Capt. Horner, to go to Horner’s house on the Long beach. Had head wind, and arrived at about 10 o’clock ; fare 25 cents! The price of going in this vessel to sea or elsewhere is 25 cents, when company is made. As I came out of the creek my eyes were arrested with a considerable mount, on which three or four large cedars were growing. It was a hill of oyster and clam shells, left there by the aboriginal Indians long since. They dried their clams. What numbers they must have consumed to have made such a hill!

Horner’s house, at which I have sat down for the present, is a new house, built and set up by a company of gentlemen in Philadelphia for the purpose of sea-bathing. It is all made for good cheer and free and easy comforts, without any attempt at elegance. None of the floors are planed, and the side walls are rough boards, and the ceilings white-washed. Its appointment of liquors and table is very good. It is set down on an extremely desolate beach, full of broken and small sand-hills, without a solitary tree. Its very desolation increased my sense of comforts! I the more enjoyed the solid diet of the table ; its zest was heightened by contrast. Its desolation too, was so isolated as to cut me off from all the world, and seemed to make me begin there an entire new existence! Thus I found charms where others might have been disgusted. But it is a manifest disadvantage that the bathers have to walk half a mile to the shore across the sand, and the ladies ride in a cart. The company intend to increase its benefits and comforts. As it has fine shooting and fishing, and a grand surf, it will always best suit gentlemen who love rough and vigorous fare. The beach is twenty miles long, and to the northward has several houses, and so much of cedar wood as to shelter red foxes. The tables are a cover which is set on trussels and moved out of the room. The room is about twenty-six by fifteen feet. The proprietors intend to build a large house next summer. [This is since done, and every thing is in more refinement.] This establishment is quite new. They have dug and found a fine well of fresh water ten feet depth near the house. It had never entered the mind of former people that good water could be found. In great sea storms, the sea has covered this whole beach, and the water came quite up to the ground floor of the house. The inlets and the beach have much altered in fifty years. It was once covered with cedar trees. Now all are gone. The inlets in the war of the Revolution admitted two frigates to come in, and now there is only water for small vessels.

This is a great place for the killing ducks and geese in the winter. They have nothing else to do, and use decoys and ambush, and very often lay out to shoot as the flocks fly over them. The house at Tucker’s beach is a cluster of three houses built at different times. The original house of the celebrated Mother Tucker is a one-story house, with a hipped roof, and front piazza. When you enter this piazza you are struck with the display of names cut in the boards of the house by the summer visitors ; and probably one hundred clams are nailed up, of large size, having names inscribed on them. The house stands about the length of five hundred feet from the seashore. The salt meadow comes close up to the house, and the house is elevated on a heap of sand and shells. The room in which I lay on my cot and write this is open directly to the ocean. I see the vessels buffeting the waves, and the roar of the bellowing surf seems to lie below me.

These beaches are much more dreary in the aspect than Cape May. Nothing seems to grow upon them but wild and scattered tufts of grass. But one feels comfort in the increase of appetite, and the consciousness of high cheer and good provisions.

How often have the landmarks of this shore been sought out by the approaching mariners of distant voyages, seeking, with anxious and distrustful eye, the first flimpse of the doubtful coast. Many this day, in the distant verge of the sinking horizon, would give great gifts to be once more on terra firma. Women passengers, sick of their confinements, listen with eager attention to the conjectures about land, which by their soundings is known to be near at hand ; and the terrors of possible stranding and shipwreck are pictured to their labouring imaginations. It might do one good to see such objects land, and to regale them with the delicacies of the season, untasted by them for months.

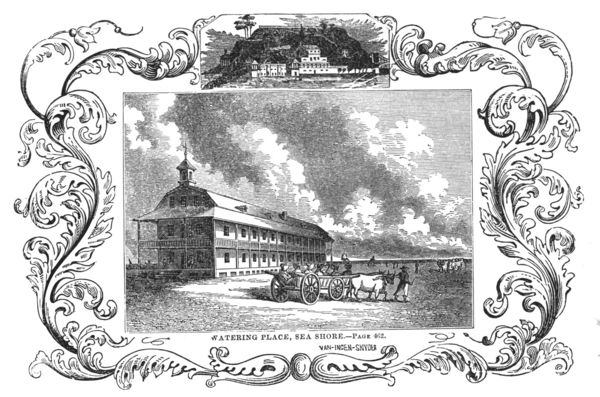

Sundry of us made a sailboat excursion up the sound to the other boarding house on the same beach, twelve miles off, to the large house, called the Mansion of Health, (of which see a picture.) We found it well kept and supported by a goodly number of inmates.

The house, a hundred and twenty feet long, stands about one tenth of a mile from the surf. The original house once there was at one half the distance, and had numerous cedar and oak trees nigh it. The great “September gale,” of 1821, swept over the whole island at this place, and tore up or blew over those trees, so that none now remain nigh, although the stumps of many are still seen. The whole island is twenty miles long, being from Tucker’s to Barnegat inlets. At is northern end are still many trees and high hills, wherein foxes burrow.

As a riding vehicle to the surf and along the beach the ladies use as ox-wagon, wherein they amuse themselves greatly in a rustic novel way.

I was surprised to learn here from old Stephen Inman, one of the twelve family residents of the place, that he and his family have ceased to be whale catchers along this coast. They devote themselves to it in February and March. They generally catch two or three of a season, so as to average forty to fifty barrels of oil apiece. I saw their look-out mast, their chaldron and furnace for rendering the oil, their whale-boats, &c. He has taken some whales of ninety barrels of oil. The whale bones of large size lay about bleaching in the sun. About his place are many oaks and holly trees. Gunners go there much, in the season, for wild geese and ducks. Inman has killed twenty-four geese in a day. Sheep, mules, and horses are pastured and browsed on the northern end of the island, by himself and others. His house having formerly been the winter quarters of the gunners, is fully cut with the names of his visitors, made on the outside boards, under the piazza.

The coasting trade along these shores must be great. Sometimes we could count twenty sail, all going onward, eastward and southward. Their white sails looked like villas along a highway.

Sometimes I think and wonder at what could have been all the features of this place before civilization and European eyes scanned it. I peopled it in imagination with Indians, seeking here and finding a summer home for their unrestrained supply of fish, shell-fish, birds’ eggs, &c. In these sounds they had often “wigwassed” for sheep heads, of whom we learnt the art of bobbing, as even now practised successfully, with flaming touch at night.

The beach at this place is certainly the best along our coast, and it be so shut up on an island, makes every thing of sea character still more like the sea-shore. The very desolation of the sands around us makes the table refreshments still more estimable by a feeling of contrast.

As we sail back to our boarding house, we notice many fish in the waters we traverse, such as we might have speared, if we had been so disposed, and had had the needful instruments.

Monday, August 17.—This begins a new epoch. Awake at five o’clock, and found the wind fair at S.W. I determine therefore to try for Long branch by sea. I am taken off in the bay to Capt. Rogers’ sloop Jane, loaded for New York, and near to the New Inlet. We arrive at New York the next day with a delightful sail.

Watson, John Fanning, Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, in the Olden Time ; Being a Collection of Memoirs, Anecdote, and Incidents of the City and Its Inhabitants, and of the Earliest Settlements of the Inland Part of Pennsylvania, from the Days of the Founders. Philadelphia, PA: Elijah Thomas, 1860. Volume II, pages 543-548.